Has Teaching Really Changed in the Forced Shift to Online?

Inside Higher Ed published an article yesterday, featuring the byline that [a] “New survey documents how professors view this spring’s mass move to virtual courses. Key findings: most used new teaching methods, half lowered their expectations for the volume of student work — and a third for its quality.” The article draws on a survey from Bay View Analytics, and purports to offer insights into the shift that colleges and universities have made en masse this spring.

According to the article, the majority of survey questions focused on how instructors changed their teaching practices, as well as their approaches to students. Given that TEACH-NOW is a graduate school of education, where we bring a laser-like focus to effective teaching, whether online or brick-and-mortar classroom, we have a natural interest in these results. Let’s take a look.

-

“A majority, 56 percent, said they had used ‘new teaching methods’ in transitioning their courses to remote delivery.” Further reading shows that 83% cited using the institution’s learning management system as their marker for ‘new teaching methods.’ Eighty percent (80%) cited using synchronous video technology (aka Zoom or Skype). As the article clarifies (correctly), the 80% figure suggests that instructors relied heavily on replication of traditional classroom lectures— they simply re-created the lecture experience using video. Key question: how does either of these items equate to instructors changing their teaching practices, or their approaches to students? A learning management system (LMS) is not a methods tool, and lecture via video is…well…still a lecture.

Perhaps there is stronger evidence for changing practice elsewhere in the article? Let’s keep looking.

-

Forty-eight percent (48%) lowered their expectations “about the amount of work that my students will be able to do.” Related to this, 32% said that they had “lowered the expectations about the quality of work that my students will be able to do.” These findings are curious. Given that these are colleges and universities, which, while they are undertaking seriously needed work around equity and access, they certainly don’t mirror the same degree of challenge that public schools engage with on a daily basis, Covid-19 crisis notwithstanding. Why, then, would instructors lower their expectations relative to the amount and quality of work? Concerns around student (and instructor) well-being could be behind such a stance (see the very end of the article, where this idea is treated almost as an afterthought), but as readers we are unsure, as those concerns aren’t mentioned in the article. What we do come away with, though, is that instructors seem to think that students can handle neither the same amount of work, nor produce the quality of work that instructors are seeking. We’d like to understand that better. Are we to understand that remote learning is so deeply inferior to traditional classroom learning that amount and quality are variables that disappear in a remote learning environment? Four-year private and public colleges led the way in this regard, with far fewer two-year colleges lowering their expectations to the same degree. Yet more food for thought.

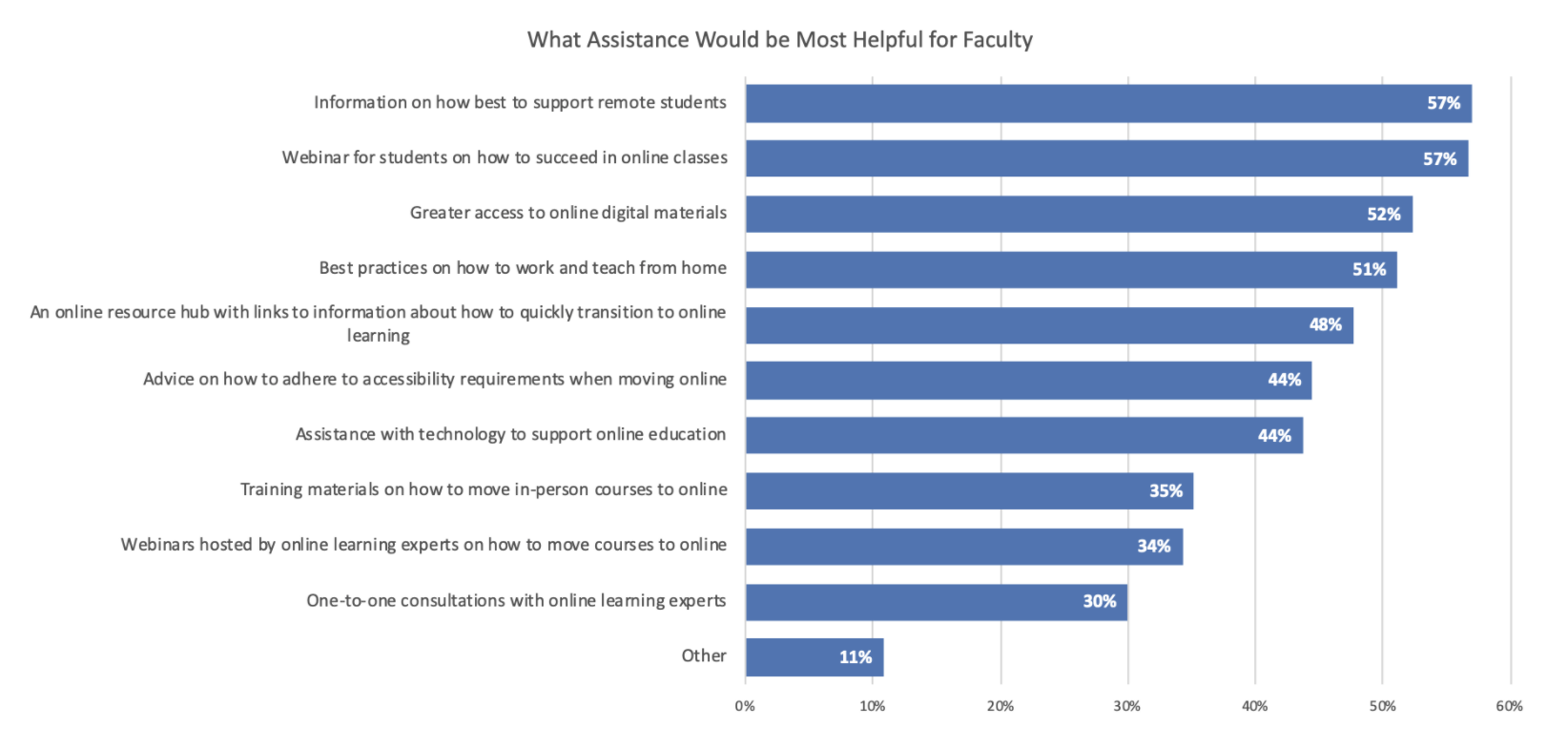

Let’s look further, to see if there is stronger (or any) evidence relative to changing practice. We will save you the time: there isn’t any. The article shifts quickly to something that could hold real value, in terms of considering teaching and learning in our current age (again, Covid-19 notwithstanding): what assistance would be most helpful for faculty? What did they themselves say that they needed (ostensibly in order to be more effective)?

What college and university instructors truly need to empower them as effective online instructors is found at the bottom of the list. They need training. Not ‘training materials’ as identified in item 8; one doesn’t simply read a manual to become an effective online instructor. The next item, item 9, is also rather curious: webinars on how to move courses online. A webinar can be a wonderfully useful tool, provided that the learning objectives and learning experiences associated with that webinar are geared toward empowering webinar attendees as users of technology, in terms of becoming resource-rich problem-solvers. Yet item 9 is, by nature, equal to item 8 — it’s the video-call equivalent of “show me the manual of how to do it.” The only item on this list that would prove transformational at the scale needed is item 10. One-to-one consultations could be powerful catalysts (so too would small cohorts), although we’d make one change to the language here…online instructional experts. The problem they’re trying to solve here is ineffective online instruction; the larger paradigm is online learning.

We are, of course, dealing with the immediate release of energy and organization around handling the current semester. What about next school year, though? Signs seem to be pointing to our need to accommodate Covid-19 as something that will come and go in waves, necessitating our flexibility to move seamlessly between classroom teaching and online teaching. As the article states, “[t]he big question going forward is what professors and colleges can do in the coming weeks to ensure that if campuses are still closed, wholly or partially, to students in the fall, they can meet what is likely to be a much higher set of expectations for quality instruction and learning.”

Let us capture that as a final thought. What about learning, as a human endeavor? How is learning affected by all that is happening? Higher education has much to learn from studies that are done at the K-12 level. Case in point: John Hattie (Professor of Education and Director of the Melbourne Education Research Institute at the University of Melbourne), in an examination of effect sizes when schools are closed, reveals what matters and what doesn’t in times of closure, insofar as ‘visible learning’ is concerned. He shares, “[I]t does not matter whether teachers undertake teaching in situ or from a distance over the internet (or, like when I started in my first university, via the post office). What we do matters, not the medium of doing it.”

There’s a lesson there for higher education, and for all of us.

Learn more about our teacher certification program and master’s in education programs.