Creating Accountability in Small-Group Learning

Small-group learning transforms the traditional teacher-driven classroom into a student-centered learning environment characterized by high engagement and achievement. By providing space for personalized learning and collaboration, small groups create a space where students receive the differentiated support they need. Teachers are often hesitant to use small-group learning due to concerns about classroom management and learning support given the multiple pods of students working collaboratively on different tasks around the classroom. How can teachers effectively facilitate learning when students are working on five or more different tasks simultaneously, especially when one of those tasks might be a teacher-led small group? How can teachers effectively administer small groups in online or hybrid learning environments?

For small groups to function well in the physical, online, or hybrid learning environment, there must be levers of accountability established and ready to employ. The following post will delve into concrete strategies teachers can use to create metrics and tools of accountability that will ultimately promote student independence, agency, and leadership in the classroom through small-group learning.

Routines and Procedures

Classrooms that function well have established routines and procedures that lead to safety and organization. Depending on the grade level and subject area of the classroom, these routines and procedures may include expectations for how students enter and exit the classroom, steps for obtaining materials, procedures for requesting permission to go to the restroom, or even ways to ask for help while working. Teachers prepare students for success and make excellent use of instructional time when they plan in detail how students should complete routine activities in class.

For small groups, teachers should consider developing step-by-step routines and procedures for any common movements or transitions that take place during small-group learning. Consider, for instance, how students may move from one small group to another in a timely and safe manner. The following common occurrences may merit the planning of a routine or procedure during small-group learning: accessing technology, obtaining and returning supplies, submitting small-group work, seeking help from the teacher, leaving the classroom to collaborate outside. In my Spanish classroom, I used the following “Workstations Rotation” procedure to empower students to lead the learning process and spend as little time as possible in transition between activities:

-

Step One: At the end of a workstation, the teacher rings the bell twice, stands up, and is seen by all students scanning the classroom. Students end conversations within 10 seconds. For students who are not on task, the teacher says, “Waiting on (specific number) of students to have their eyes silently on the speaker.” Then the teacher uses positive narration to call out those who are on task: “Thank you (insert name) for your attention.”

-

Step Two: Once all students are silent and have their eyes on the teacher, the teacher says the following instructions in an even tone and a moderate volume: “When I say go and not before I say go, quietly wrap-up conversations, pack up materials and prepare to transition. You have 60 seconds on the timer. Go.” The teacher sets and displays a timer and is seen scanning the room or walking around. (Note that the teacher is careful never to speak while students are talking. If students start talking during instructions, the teacher self-interrupts. If a student is not paying attention, the teacher uses close proximity. If a student is wildly off task, the teacher interrupts the transition and tells students to continue working momentarily until the issue can be resolved privately and individually.)

-

Step Three: At the end of the timer, the teacher rings the bell twice and is seen scanning the room. Once all students are silent and have their eyes on the teacher, the teacher says the following instructions in an even tone and a moderate volume: “When I say go and not before I say go, stand up, push in chairs, walk silently to the next workstation. You will have 15 minutes to work.” Before saying go, the teacher does a choral check for understanding: “We will stand… (students chorally complete the sentence). We will push in our… (students chorally complete the sentence). We will walk… (students chorally complete the sentence).” The teacher says, “Go.” Then the teacher sets and displays the timer and is seen scanning the room or walking around. (Note that the teacher uses positive narration to point out students who are following directions. For students off task, the teacher gives quick verbal reminders in a private and respectful way. If a student is consistently missing the mark, the teacher has a private conversation and practices transitioning.)

-

Step Four: Once all students have arrived at their next workstation, the teacher circulates through stations and assists where needed. Any students who may have struggled during the transition are given a chance to meet with the teacher.

As detailed and specific as this may seem, the procedure I have just described helped my classroom function like a well-oiled machine with little or no disruption due to unwanted behavior or confusion. Students spent the vast majority of their time working independently and collaboratively in small groups because we wasted no time on messy transitions.

Within virtual and hybrid learning environments, it is important to step back and consider the specific context in which learning occurs. Each environment will require different routines and procedures to function properly; however, a few best practices remain true for any effective routine. According to Doug Lemov’s groundbreaking manual for effective teaching and learning, Teach Like a Champion 3.0, highly effective classroom procedures have the following characteristics: simple, quick, requiring little narration by the teacher, and planned in detail. One invaluable tool for small-group instruction online is called “Breakout Rooms,” virtual spaces in which a large group of participants in a virtual meeting are split into smaller groups temporarily. This feature is available through the Zoom and Microsoft Teams platforms. Click here to read a comprehensive article on best practices for managing breakout rooms in Zoom, and click here for the same resource for Microsoft Teams. What routines and procedures are essential for small-group learning in your classroom?

Clear Instructions

Students need access to age-appropriate instructions to guide them in small-group learning. Depending on students’ grade level, these instructions may come in writing, pictures/images, or even video. (Consider the impact of combining two or more of these formats for increased student comprehension through multimodal instruction, especially for students with special needs and students with language barriers!) Some best practices to consider in developing clear instructions include writing concisely, eliminating extraneous steps, and integrating flexibility by providing multiple options. Teachers must provide students with easy access to instructions for any small-group task. In the physical classroom, this might be done by providing small-group work binders with specific instructions and materials at the ready; however, in hybrid environments teachers might create tasks on Google Classroom or another learning platform that students can access from their personal computers or tablets. Then students can work in small groups through breakout rooms in Zoom or Teams meetings while the teacher monitors each group periodically. (Note that students can record their breakout rooms and upload them as evidence of their collaboration as permitted by school and district policies.) One way or another, students need access to clear and concrete instructions for small-group tasks that require little or no teacher involvement.

While step-by-step directions are essential for some tasks, teachers must also consider the ways in which clear instructions provide space for students to engage in higher-order tasks that might require collaborative problem solving, synthesis of knowledge and ideas, or even the creation of a new process or product. For this, teachers craft guiding questions that inspire students to engage deeply with the topic at hand by connecting to students’ interests and passions or even allowing students to relate back to their own lives. Using guiding questions as a springboard, students become steadfast explorers and collaborators who are excited to learn. Below are examples of effective guiding questions for small-group learning:

-

Mathematics: How might you model (insert mathematical concept or theorem) using the materials and resources available at this workstation?

-

Social Science: What constitutes a good home? How can governments, charities, and other institutions contribute to people’s access to good homes?

-

Language Arts: How is the theme of this text relevant and important to folks today? What can we learn and apply in our lives immediately from this text?

-

Physical Science: How is your life affected by the laws of motion? Provide examples for each law of motion.

-

Biological Science: What can we apply from our most recent unit of study to promote awareness of the importance of handwashing? How might you present this information to the general public?

-

World Languages: What are the keywords you would need to learn to communicate effectively about (insert topic) in our language of study? What strategies would best support you in learning those words?

-

Fine Arts: How do musicians improve the quality of their compositions and performances? What examples can you provide to support your analysis?

-

Physical Education: What routines and habits from your daily life contribute to your overall wellbeing and health? Conversely, what routines and habits might negatively impact your overall wellbeing and health?

While teachers may choose to develop a task aligned to a guiding question, they may also choose to allow students to be agents of their learning as they develop their own unique responses. In my Spanish classroom, students often developed innovative, creative, and unique projects in response to guiding questions I provided in each of their student-led small groups. Some examples of the types of tasks that students proposed and completed in Spanish class are a classroom newspaper, a hydroponic garden, a cooking show, and even a trip to a local Spanish mission. In the online Spanish classroom, students wrote dramatic skits, recorded group podcasts, and developed computer games in their small groups. Using these guiding questions as starting points for small-group work, students can tap into their own interests, opinions, and perspectives.

Student-Facing Rubrics

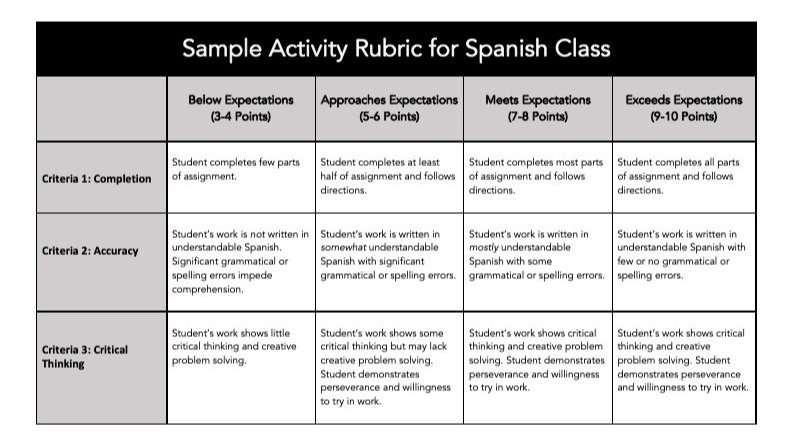

Rubrics are a powerful form of accountability that allow teachers and students to work from a shared understanding of the learning outcomes of any small-group learning opportunity. A rubric is an evaluative tool that includes a set of learning criteria and performance levels that are equally applied to all students in a given task. According to EdGlossary, an online resource defining common academic and school-improvement concepts, “In instructional settings, rubrics clearly define academic expectations for students and help to ensure consistency in the evaluation of academic work from student to student, assignment to assignment, or course to course.” Rubrics clarify expectations and help create consistency within the evaluation process. Check out the resources below designed to help teachers create their own rubrics:

In the small-group learning environment, rubrics can be used throughout the learning process. Teachers must provide students with access to rubrics either in paper or electronic formats that are easily accessible throughout the learning process, not just at the end. Students at the start of an activity or assignment might be invited to review the rubric in order to plan their work and set collaborative goals as a team. While they work, students might refer to the rubric as a self-monitoring tool. Finally, rubrics allow teachers to provide data-rich feedback to students during and after small-group work by highlighting achievement and growth opportunities in alignment with performance levels detailed for each rubric criteria. The following is an example of a generic rubric I used in my Spanish classes for any small-group assignment students completed in both physical and virtual learning environments. I would make changes and adjustments for specific tasks. This rubric enabled me to create a student-c learning environment through small groups.